Arctic tilting doll: How to revitalise the economy of a small and remote border town

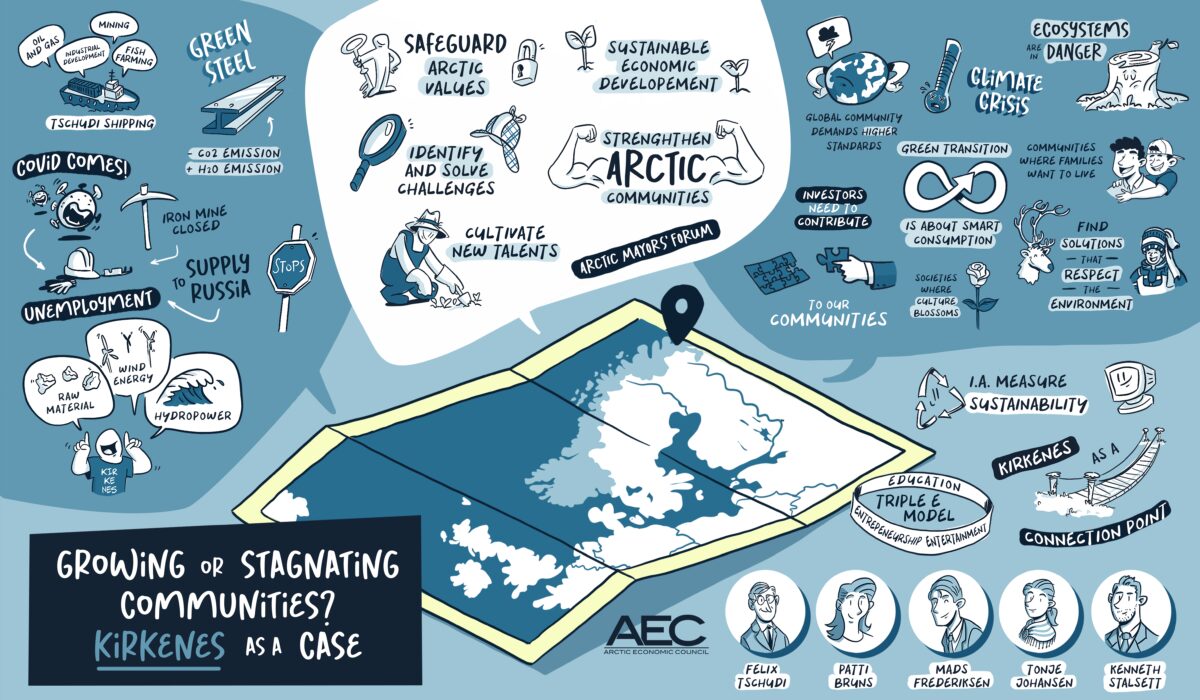

One could describe the economy of Kirkenes with an image of a tilting doll. After being hit and pushed down, it always rises back up. Today, the border town in the north of Norway is again facing challenges outside of their control.

The local population is aging and rapidly decreasing. In 2021 on average, one person left the municipality every second day.

Kirkenes is a town of 3500 people in Northern Norway. It takes more than two hours to fly south to the capital Oslo, but only 20 minutes to drive by car to the Russian border in the east, and around 40 minutes to drive to Finland in the west. Kirkenes has a diverse population where many people have Saami, Finnish, and Russian origins.

Like any real estate agent will tell you, the most important thing is location, location, location and Kirkenes’s location in the high night and close to its neighbours has been both a blessing and a curse throughout history. Now, a new generation is trying to revitalise the town by developing the area into a place of entrepreneurship, education, and entertainment.

To understand the future of Kirkenes, we have to understand its past. The town in Northern Norway has felt the ghosts of history as well as the spirits of hope. As this essay will show, the region is on the path to a new adventure within shipping, tourism and the green transition.

International trade hub through the centuries

The history of economic development in Northern Norway is closely connected to the Pomor trade, a barter trade of fish in exchange for flour and wheat between the North-west of Russia and Norway. The trade reached its peak during the Napoleonic wars, as it was one of the very few channels for the Norwegians to buy grains through due to a blockade from Great Britain.

The indigenous Saami people were also freely traveling and trading between Norway and Russia. International commerce grew the regional economy and attracted more people to come and settle in the area around Kirkenes. Many of them came from neighbouring Finland.

Kirkenes was established in 1862 and at that time was a fishing village. But in the beginning on 1900s iron deposits were found and the Sydvaranger mine was opened in 1910. Meanwhile, the Pomor trade slowed down and stopped completely after Russian revolution when the ties with Russia were cut.

Destroyed and rebuild

During the Second World War, Kirkenes was one of the main bases for both the German navy and air force in the north, and the key logistic hub for anything going to the Russian front. The town endured more than 320 attacks from the air, and when the Soviet army liberated the town in October 1944, the Germans had scorched most of Kirkenes down to the ground, leaving only 13 houses standing. Today, there still stands a statue of a soviet soldier to commemorate when their Eastern neighbours liberated the town. Like a phoenix, the town rose from the ashes and grew. After the war, the Marshall Plan funding from the government allowed the main industry to soon got back on its feet again.

The Sydvaranger mine was the largest mine in Norway for decades. During the 1950s and 1960s, it was iron from northern Norway which contributed to the reconstruction of Europe, and so at that time, the mine was highly profitable.

Rebuilding Russia

The fall of the Iron Curtain prompted a lot of optimism amongst Kirkenes locals to rebuild economic ties with Russia, as suddenly, the small and remote Norwegian town found itself right at the border to the market with over a million people. This was the population of the Murmansk region at the beginning of the 1990s. The Russian fishing vessels started to land their catch in Norway and would then stay for repair and maintenance. Norwegian service companies got strong aspirations for natural resource development in Russia. What is more, lower labour costs in Russia were attractive to Norwegian companies.

Barents Cooperation

The new course for cooperation across borders paved the way for the signing of the Kirkenes Declaration in 1993 and the establishment of the Barents-Euro Arctic Council to facilitate intergovernmental dialogue between northern regions of Finland, Norway, Sweden and the North-west of Russia. International Barents Secretariat and the Norwegian Barents Secretariat were established in Kirkenes to build bridges between people and economies of the region.

Slashing the iron prices

At the same time, the mining business was not doing well. The Norwegian government held control over the Sydvaranger mine until 1997, as it was seen as an asset of significant strategic regional importance due to its close proximity to Russia. However, falling iron prices meant that it was eventually forced to close down.

The hope of a new mining fairy-tale returned when a new company took over the mine from 2009 until 2015, with more than 250 million USD being invested in the production. During the peak periods of the mine, more 1500 people worked there, and it was the economic heart of the town. The closure led to around 400 people losing their jobs in the small Kirkenes community – while it is estimated that 300 persons lost their jobs in the supplying industry. Today, about 30 people work to reopen the mine and maintain the remaining equipment.

If the prices for iron ore goes up mining operations will again become attractive in the north. New investors can come in, the processing plant could reopen, and in total generate up to 450 new jobs. Even though Kirkenes in the past was built on mining, the future opportunities are more diverse today.

Smartphones and Northern Lights

In 2007 and 2008, two things had a positive impact on Kirkenes’, at the time, small tourism industry. The first phenomenon was the invention of the iPhone. In 2007, it was suddenly possible to take good photos with your smartphone. Tourists began to take pictures of the northern lights, which in an instant, were shared around the world via social media. The second phenomenon was the release of a popular BBC documentary. In 2008, the English actress Joanna Lumley travelled to northern Norway to hunt the northern lights. She managed to see them and so did the six million BBC viewers. This is how the northern light tours became popular.

The whole world comes to Kirkenes

At the same time, the Norwegian company Hurtigruten started to focus on tourism too and became more than just a transport company. They began to sail all year round. Airlines were catching up and opened new flight routes. Suddenly, the locals in Kirkenes set out to explore opportunities for tourism which they had not considered before. They started to run King Crab safaris, where tourists could now go and catch and cook the local king crab in the Arctic waters. Tourists could also embark on an Arctic bird safari or spot the World War Two installations.

Due to Kirkenes’ unique location, close to Russia and Finland, tourists could suddenly experience more of the north in a shorter time. Tourists would drive from Finland to Kirkenes, and cruise ships would stop in Kirkenes before going sailing into the Russian Arctic. The rapid development of tourism in Finland benefitted the small Norwegian town and so did the success of Norwegian locations like Lofoten, Tromsø, and Svalbard, as everyone wanted to experience the raw Arctic nature.

However, tourism is still a small industry, with only 20 companies as members of Visit Kirkenes. Together they attract round 19.000 visitors per year. During the boom years from 2014 until 2019, the tourism industry in Kirkenes had a turnover of around 70 million Norwegian kroner. Value creation was high as a tourist was on average staying for just 1.4 days during their visit.

Covid lockdowns Arctic business

On 11 March 2020, the WHO declared the corona pandemic which would impact everyone, but especially those in small remote border communities who depended on cross-border cooperation.

The Saami, an Indigenous people living across the North of Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Russia, were affected both socially and economically by the lockdown.

The pandemic also had a severe impact on the tourism industry, which was forced to adapt to changing circumstances. Now the local citizens in Kirkenes were offered special discounts to stay at the local snow hotel which was originally built for tourists. The cruise ships stopped arriving and the borders closed down. This resulted in fewer individual travellers and consequently drove smaller tour operators out of business.

As Covid stepped back and the traveling restrictions started to ease, optimism again returned to Kirkenes. The tourism industry experienced a rapid surge and people could journey across national borders again.

War shuts down Russian ties

In January 2023, the region can celebrate the 30-year anniversary of the Kirkenes Declaration. Signed during the conference on cooperation in the Barents Euro-Arctic Region, it established new partnerships between the Nordic countries, EU, and Russia.

The declaration states that “The Participants recognized the importance of increased economic cooperation in the Region in the form of trade, investment, industrial cooperation, etc”

Since the 1990s, a number of companies in Kirkenes have based their business model on their proximity to the Russian market. Companies would set up production in Russia and sell through Norway, whilst Russians would also cross the borders to come and work in Kirkenes.

Much of this activity ended abruptly in the spring of 2022. The war in Ukraine has made all relations with Russia tense. Norway is trying to balance between being an integral member of NATO while also honouring fisheries management agreements with Russia and keeping the borders and ports in Northern Norway open. However, tour operators have stopped going to Kirkenes due to the close geographical proximity to the Russian border, and the closure of the air space has also led to less Asian tourists traveling to northern Norway.

The competitive advantages of cross-border collaboration are now vanishing, putting around 600 jobs related to Russian markets are risk. For years, the companies and citizens in Kirkenes have been encouraged to trade with their neighbours, and small Barents families have been created. The economic sanctions against Russia have hit the town particularly hard. As one business owner said, “Before we had to learn Russian, now we have to learn (to operate) law”. Before the war, the Norwegian Kimek shipyard attained more than 70% of its turnover from servicing Russian vessels. If Norway closes their harbours completely, the shipyard with 80-90 man staff will have to close down at the minute.

During the first months of the war, the Norwegian officials displayed strong support for their northern areas. In mid-March, Norwegian Minister of Finance, Vedum and Minister of Business, Vestre visited Kirkenes and announced an aid package to help the community. Prime Minister Støre visited the town in May and stated, “The government must contribute to the transition, because what is happening now could continue for a long time.” He also acknowledged that the northern municipalities of Norway are being hit the hardest both in terms of people and businesses due to the cut-off from the Russian market. Afterward, Kirkenes was visited by Minister of Defence, Gram. This visit recognized the security implications of bordering Russia during this time.

The changing relationship with Russia is not the only problem for Kirkenes. Higher fuel prices also mean that less tourists are willing to drive the extra mile up north to visit the town. The supply chain crisis has also had a negative impact on what is being sent up north.

New realities, new economy and more people

So what does Kirkenes have to offer now? If the global recession is avoided and China experiences a construction boom again, perhaps the iron ore prices will go up and the Sydvaranger mine can be reopened. But what if it doesn’t?

Sør-Varanger Utvikling, the municipality’s development company, believes that Kirkenes has the potential to become a green growth town by 2030, with the creation of more than 12.000 jobs. The challenge here is not so much a lack of ambitions but rather a lack of people. The whole municipality currently has more open job postings than there are unemployed people. Another business owner said that he had ten open engineering positions and would be happy if he could manage to fill five of them – with last year’s engineering students.

Reinventing identity with Finnish investors

In 2018, the old hospital in Kirkenes was replaced with a new modern one, leaving 22 000 sqm of empty space. Now, investors have bought the old hospital building and want to transform it into a place of innovation. Their ambitions are big, they want to use the building as a test site for new renewable energy solutions. The investors want to develop a creative place for people to study and to develop new companies. It is to be a place of peace and quiet, to do your “work away from home” or “workcation”.

Local partners are developing the project alongside Finnish investors and they hope that they can break the negative trend in demographics in the region, and help boost the economy after the impact of the reclosure of the mine, the pandemic, and sanctions against Russia.

Kirkenes – the Arctic port of Finland

The port of Kirkenes is also looking towards Finland and wants to attract some of the Finnish exporters of raw materials. The Norwegian port has an advantage because it is ice-free and is closer to the Asian markets. While Finnish ports in the Gulf of Bothnia are further away and have challenging ice-conditions in wintertime. What is more, Kirkenes will have access to the green hydrogen and ammonia from the neighbouring municipality of Berlevåg, where the hydrogen factory and a wind park are already in place.

Way forward

Kirkenes has experienced a great deal of misfortune in recent years, nevertheless, there are many areas of opportunity for the region to develop and invest in.

Waters around Kirkenes host a unique bird life, and there is significant economic potential surrounding the market for king crab. The region has access to renewable energy production and is perfectly located for maritime logistics in the Arctic. Finally, the town of Kirkenes has proved that they are not willing to give up, even when they are tilted over – they will stand back up and endure.

The Norwegian government coalition agreement, Hurdalsplatformen states that “the northern areas are Norway’s most important strategic sphere of interest” and that the government aims to “renew and strengthen the work in the north…to stop the negative population trend, use the local values to create growth and make the northern areas a centre for the green transition.”

This commitment from the Norwegian government is now more important than ever.